Changeist (formerly Big Citizen Hub), a Community Partners project since 2014, has recently been recognized on both the state and global levels. The project, which works to expand the social capital of young people and mobilizes youth to explore the issues they care about most, has been tapped by the office of Governor Gavin Newsom to be part of the Governor’s 9-point plan to increase civic engagement of Californians, and project leader Mario Fedelin has been named an Obama Foundation Fellow, which supports civic innovators around the world. Changeist’s co-founders Beth Bayouth and Mario Fedelin say evaluation has been a huge factor in setting them apart, so we thought it would be interesting, instructive, and hopefully inspiring to fellow project staff to learn more about how Mario and Changeist’s Chief Impact Officer, Manijeh Mahmoodazeh, are using data collection and evaluation to change the organization.

Embrace learning, not fear.

When Mario and Beth began developing the organization in 2013-2014, a primary goal they set was to stand the test of time. They saw many youth development organizations created in the 1980s and ‘90s (and earlier) struggling to exist and remain relevant because they were resistant to signals around them indicating a need to change for current times. Mario wanted to figure out “how to not be fearful of evaluation but instead use it to change us.” He would face that challenge head-on just five years in. As Big Citizen Hub, the group originally intended to redefine the word “citizen” based on what it means to be invested in one’s community. But because the word “citizen” has become politicized, and even weaponized in the U.S., it spawned a lot of tension among youth participants and their parents. Feedback loops and data points were letting the organization know that the change in definition they were seeking just wasn’t happening in the current politicized climate. Instead of fearing what the data were telling them, the project leaders listened and chose to make a responsive pivot: they rebranded as Changeist. Mario describes this as one of the small ways they’re using information, but it’s really big, as is the shift in thinking it takes for some people to stop being afraid of interacting with data. This is one way Mario and Beth have created an organization unlike any they had ever worked in before. To keep the focus on learning, rather than using evaluation to judge and punish those who “fail,” Manijeh explores process questions with the team. They look at not just if the program works, but how it works, why it works, for whom it works, under what circumstances it works. Talking about the process moves away from the binary of success or failure, while still highlighting positive program aspects to amplify, as well as areas for growth.

When Mario and Beth began developing the organization in 2013-2014, a primary goal they set was to stand the test of time. They saw many youth development organizations created in the 1980s and ‘90s (and earlier) struggling to exist and remain relevant because they were resistant to signals around them indicating a need to change for current times. Mario wanted to figure out “how to not be fearful of evaluation but instead use it to change us.” He would face that challenge head-on just five years in. As Big Citizen Hub, the group originally intended to redefine the word “citizen” based on what it means to be invested in one’s community. But because the word “citizen” has become politicized, and even weaponized in the U.S., it spawned a lot of tension among youth participants and their parents. Feedback loops and data points were letting the organization know that the change in definition they were seeking just wasn’t happening in the current politicized climate. Instead of fearing what the data were telling them, the project leaders listened and chose to make a responsive pivot: they rebranded as Changeist. Mario describes this as one of the small ways they’re using information, but it’s really big, as is the shift in thinking it takes for some people to stop being afraid of interacting with data. This is one way Mario and Beth have created an organization unlike any they had ever worked in before. To keep the focus on learning, rather than using evaluation to judge and punish those who “fail,” Manijeh explores process questions with the team. They look at not just if the program works, but how it works, why it works, for whom it works, under what circumstances it works. Talking about the process moves away from the binary of success or failure, while still highlighting positive program aspects to amplify, as well as areas for growth.

Don’t separate evaluation and program development.

For many people the word “evaluation” brings to mind surveys that are administered at the end of a program to help determine if the program achieved its goals. This kind of delayed and linear evaluation has long been a source of frustration for many social innovators who want more rapid learning loops to help them adapt in real time. Instead of waiting until the end of a program to engage with an evaluator, leaders of initiatives addressing complex social issues find an embedded approach more useful. Engaging with an evaluator is an expense many CP project leaders think they can’t afford, but Mario sees it as an investment in the ongoing health of the program. Program development and process evaluation are so tightly woven that, for them, it’s all just programming. They use mobile surveys to collect data each week in real time, and their weekly analysis of those data informs how they engage with their youth participants and structure their program for the next week. It was this approach that also caught the attention of leaders in Sacramento. Governor Gavin Newsom’s office was so impressed by how Changeist collects and uses data, they invited the project to expand into an AmeriCorps program in multiple California cities. In 2019 Changeist is bringing its program to Stockton and growing the number of young people its LA program serves. In 2020 they’ll expand into another Central Valley city. Case-making is not Mario’s primary interest in data and evaluation, but he does admit that having Manijeh at the meetings with Governor Newsom’s team made it really easy to talk about why the program works: “The amount of research that we put into our program to make sure we’re doing the right stuff and that we’re looking at the right stuff and we’re responding to the right stuff, that is what made the case kind of bullet proof.” Their primary interest in gleaning information, however, is so that evaluation is another part of their program that empowers youth to share their voice, to feel more comfortable to show up as their whole selves, and to exercise their right to self-determination.

For many people the word “evaluation” brings to mind surveys that are administered at the end of a program to help determine if the program achieved its goals. This kind of delayed and linear evaluation has long been a source of frustration for many social innovators who want more rapid learning loops to help them adapt in real time. Instead of waiting until the end of a program to engage with an evaluator, leaders of initiatives addressing complex social issues find an embedded approach more useful. Engaging with an evaluator is an expense many CP project leaders think they can’t afford, but Mario sees it as an investment in the ongoing health of the program. Program development and process evaluation are so tightly woven that, for them, it’s all just programming. They use mobile surveys to collect data each week in real time, and their weekly analysis of those data informs how they engage with their youth participants and structure their program for the next week. It was this approach that also caught the attention of leaders in Sacramento. Governor Gavin Newsom’s office was so impressed by how Changeist collects and uses data, they invited the project to expand into an AmeriCorps program in multiple California cities. In 2019 Changeist is bringing its program to Stockton and growing the number of young people its LA program serves. In 2020 they’ll expand into another Central Valley city. Case-making is not Mario’s primary interest in data and evaluation, but he does admit that having Manijeh at the meetings with Governor Newsom’s team made it really easy to talk about why the program works: “The amount of research that we put into our program to make sure we’re doing the right stuff and that we’re looking at the right stuff and we’re responding to the right stuff, that is what made the case kind of bullet proof.” Their primary interest in gleaning information, however, is so that evaluation is another part of their program that empowers youth to share their voice, to feel more comfortable to show up as their whole selves, and to exercise their right to self-determination.

Know what’s important to you.

Knowing what’s important to you is the first step in finding the right evaluator (or any collaborator). Mario is a creative and critical thinker who knew he wanted to work with an evaluator who would be up for trying things that are cutting edge or methods that others might view as “backward.” Manijeh’s values, priorities, and work style were the right fit for the organization. Her out-of-the-box thinking led her to adapt a method that was used in academic research but never in programming to create Changeist’s mobile surveys. Knowing what’s important to your organization lets you operationalize your organizational values. Evaluators often help organizations not only define and articulate their values or guiding principles, they also uncover where the organization’s activities are supporting (or not) the goals of enacting those values. Changeist’s organizational values inform all of their decision-making processes, including their development strategies. So, as Mario points out, there is a direct connection between evaluation and how and from whom they seek support. Perhaps most importantly, Changeist works hard to keep themselves youth-centered. Their evaluation processes aim to create an environment where their young people feel empowered to share their voices. Evaluation helps cultivate a culture in which the program designers and implementers are holding themselves accountable to the program participants. Evaluation keeps the organization responsive, relevant, and youth-centered.

Advice to project leaders thinking about engaging with evaluators

Mario: The first step is wanting it. Having the idea of wanting to use information. A barrier for peers in the youth development space is that they don’t find worth in information. Take a first step, and start with what may feel most comfortable. Once you feel comfortable with the idea of using information, then you can start to stretch, and the evaluator might be able to convince you to do the right thing or the different thing or the scary thing.

Manijeh:

- Don’t be afraid to ask the obvious question. Sometimes you can overthink things too much in the evaluation process and forget that asking a young person if they’re having fun right now while they’re at your event or experience is valuable data in and of itself.

- In working with your evaluator the first step should be taking a real and honest look in the mirror and trying to figure out for yourself: Do we have systems in place that can change? Am I, as one of the people with power in this organization, someone who is OK with hearing about my shortcomings and my program/baby’s shortcomings? That’s what’s going to make evaluation meaningful — being able to accept the places where growth needs to happen and then having the drive to do the best possible. Make sure that folks feel comfortable in your space to be honest, to give you feedback and data, and to use it.

- People tend to think that data is just numbers that come from surveys, but data is everywhere in your organization. It’s also what your staff tells you, it’s also what the people experiencing your program tell you. So start thinking about data more openly, in that it’s not just the formal sources, but it’s also your employees’ perspectives. That is data in and of itself, but it often doesn’t have formal avenues to get to you.

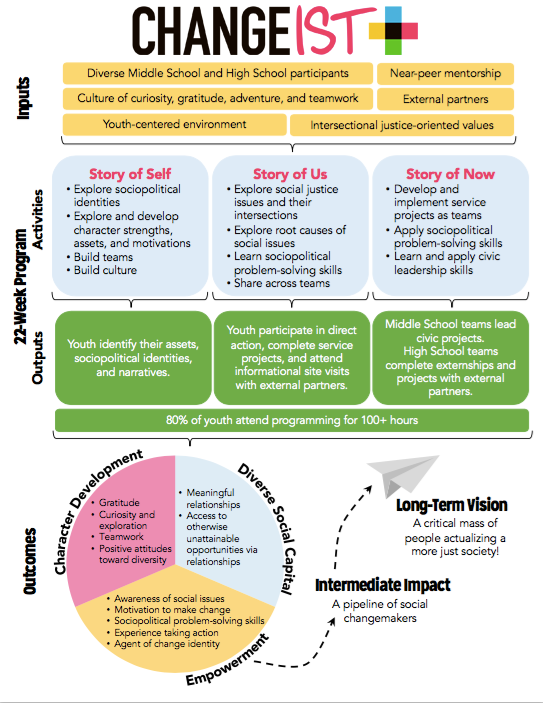

Extra bonus for project leaders who dread having to create a logic model only because funders are asking for one: Check out how the Changeist logic model contributes to telling the story of their programs and the changes they’re aiming to create.

Chikako Yamauchi, a program evaluator and Mellon/ACLS Public Fellow at Community Partners, has over 15 years of nonprofit experience in the arts, research and evaluation.

Photo credit: Beth Bayouth